Divided by Design

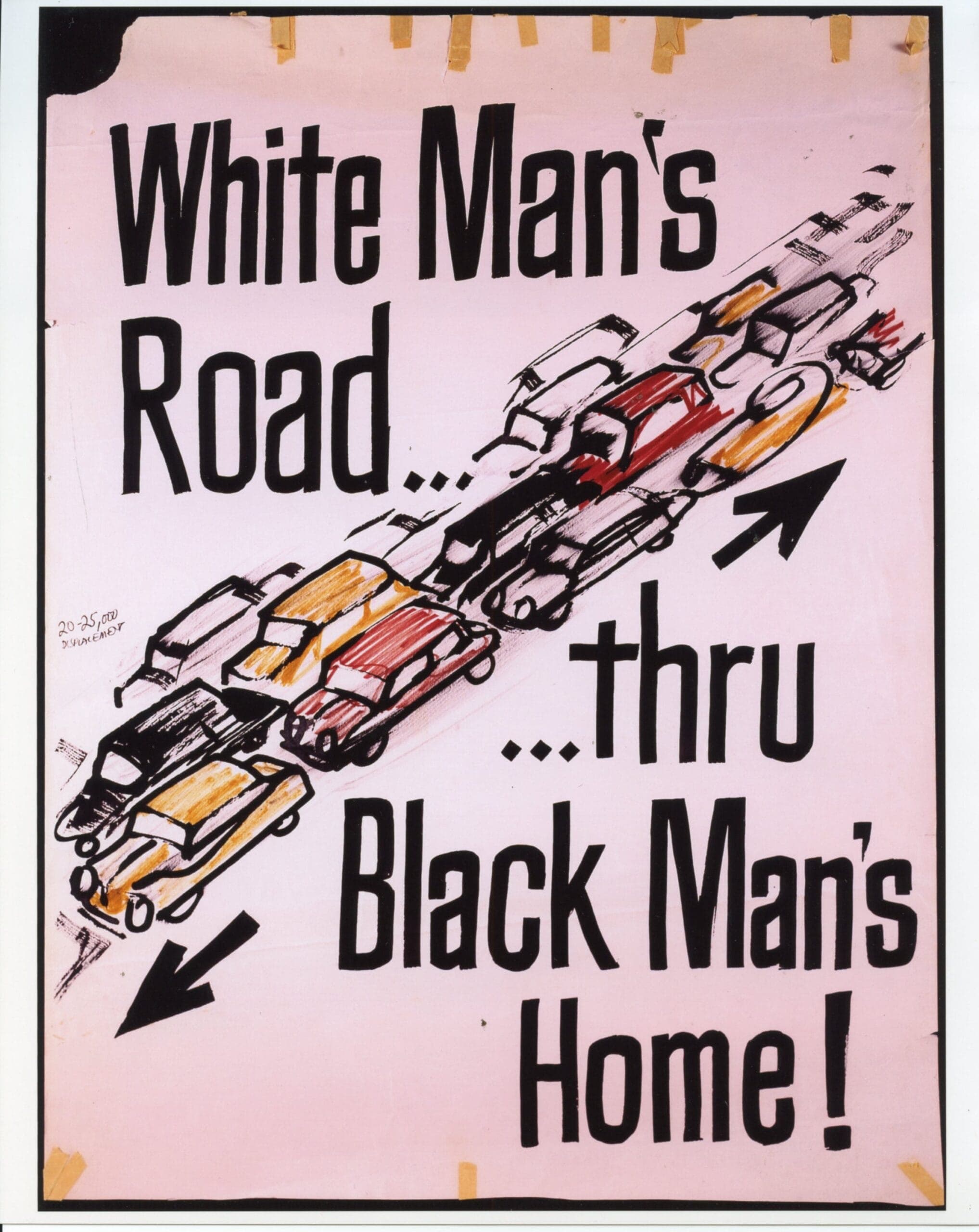

Low-income communities and communities of color have been and continue to be disproportionately harmed by our approach to transportation in the United States.

This damage has come in many forms, but most egregiously through the construction of the Interstate Highway System. A growing understanding of this reality helped lead to the creation of new provisions and programs aimed at undoing some of this damage in the November 2021 infrastructure bill. But these steps were modest and policy interventions continue to focus largely on past harms or making small, insufficient reforms. All of which ultimately fails to grapple with the reality that the fundamental approach of our current transportation program creates and exacerbates inequities.

Past decisions, including routing the Interstate Highway System through communities of color, dividing and often demolishing them in the process, still shape our built environment. And most importantly, the foundation of the modern transportation program was built on models, measures, and standards with roots in this era.

Without a fundamental change to the overall approach to transportation, today’s leaders and transportation professionals, no matter their intent, will perpetuate and exacerbate the damage.

A guide to this report

After a brief introduction below, Part I examines the damage and inequities deliberately created by and in the federal transportation program from ~1950 onward. It concludes with a unique analysis of both an unbuilt and built highway segment within Atlanta and Washington, DC to quantify what was lost, who bore the brunt of the damage, and what could have been lost with highways that were never built.

-

Part II examines our current transportation program to demonstrate how the programs, standards, models, and measures have their roots in the previous era and exacerbate inequities—whether intentional or not.

-

Part III outlines what needs to change—concrete steps we can take to fundamentally reorient the program around unwinding those inequities.

You can download and read the full report as a PDF.

This video, drawn from content in Part II, explains how modern federal guidance on estimating the value of time helps justify the hefty price tag of destructive, divisive highway projects.

The divisions aren’t felt equally

Wide, heavily trafficked roads with subpar or non-existent sidewalks and few places to cross safely make walking or biking unpleasant at best and deadly at worst. For people with impaired vision, mobility, or cognitive ability, navigating these communities can be impossible.

These two systems reinforce each other: sprawling development requires wider roads to move people, almost all of whom have to drive between spread-out destinations; and wide, fast roads require so much space to move and store the cars that development is forced to sprawl even further apart. The result is both predictable and expensive: necessities move further away and reaching them costs more in terms of money and time.

Approximately 28 million Americans (about nine percent of the population) do not have access to a car, and lower-income people and people of color are more likely to not have access to a car. This is not just an urban issue. In fact, the majority of counties in the U.S. with high rates of zero-car households are rural. And too often policymakers dismiss the transportation needs of rural Americans by assuming that everyone has cars and is happy to spend vast amounts of their time and money on driving.

We can and must do better.

Merely making tweaks to our approach will fail to correct fundamental problems

The widely accepted approach to addressing the destructive flaws in our transportation system has been the same for years now: make small, additive reforms, while failing to change the underlying program, standards, or practices. On the project level, this is akin to adding a bike lane and sidewalk along a dangerous road that is never changed.

On the program level, it’s done by routinely creating small new programs to improve problems that are being actively reinforced by the billions contained in the conventional federal transportation program.

A Patchwork Solution Won't Cut It

A System in Need of a Reboot

While the federal government has direct control over only a small amount of discretionary funding, they do control roadway design standards, models and tools, and performance targets that states rely on every single day.

States, which control the lion’s share of all transportation dollars, have immense flexibility to try something new that might get better results. The question now is whether elected leaders at the state and federal level will settle for more of the same or demand that USDOT and state DOTs reorient the transportation program to provide all people access to jobs and services no matter their location, financial means, or physical ability.

If our elected, appointed, and civil transportation decision-makers fail to understand how current USDOT guidance and state DOT actions are still actively harming low-income people, people of color, older people, and people with disabilities, they cannot begin to truly rectify these injustices. (As spelled out in Part II)

Their intent to do things differently or better than their publicly racist forebears in the 1950s and 1960s is irrelevant when many of those previous practices are still deeply embedded in the transportation policies and standards of today. Today’s leaders must understand how the past is still shaping current practices. They must reevaluate how their decisions are made and who their decisions serve.

Congress and the federal government are right in part: it is time to fix the harms of our transportation system, but creating tiny new programs will fail to address the damage.

We need a new approach.

© 2025 Smart Growth America. All rights reserved

Site By3Lane Marketing