Divided by Design

Examining the damage in Atlanta

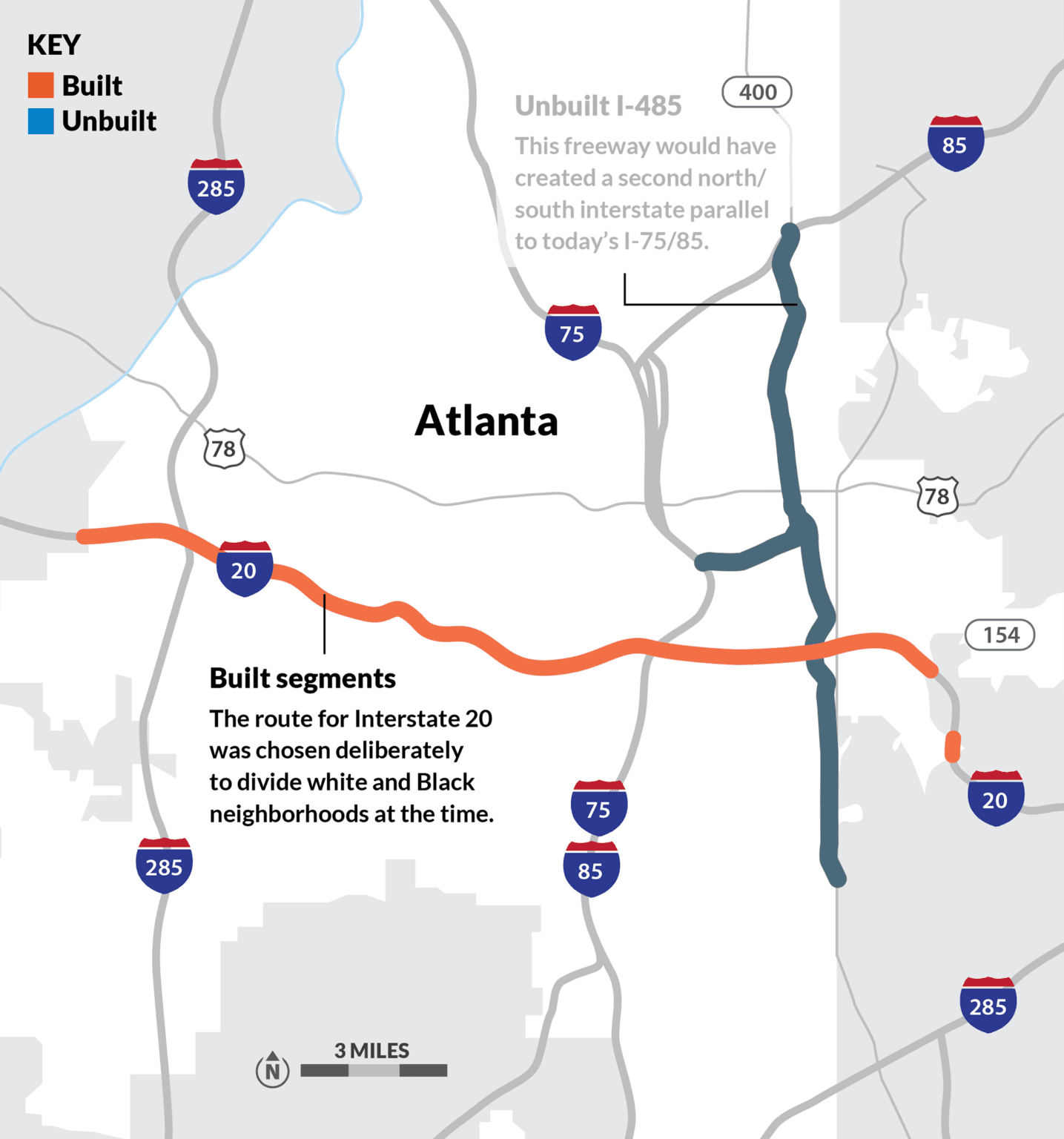

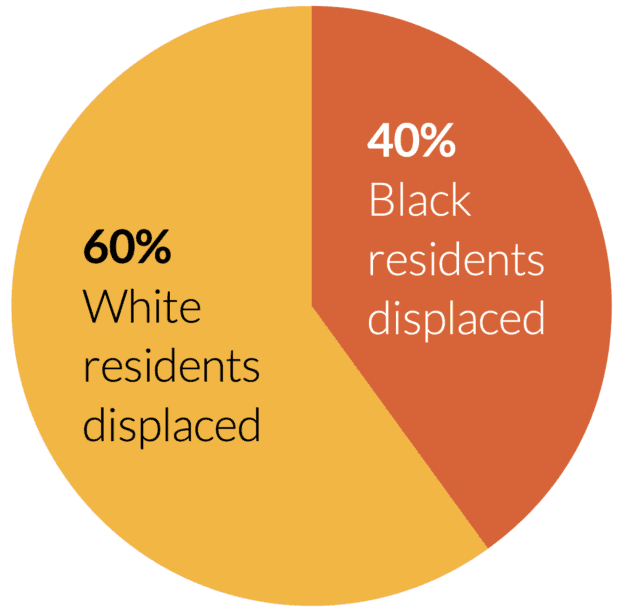

The devastation, disconnection, and displacement of highways plowed through cities and neighborhoods is easy to see, but rarely do we quantify the costs in terms of lost wealth, land, residents, and businesses. The damage also could have been much worse, with many planned highways never built or completed. We examine current and historical data on the impact of one built and one unbuilt highway in Atlanta.1

Atlanta's Story

I-20 (built) and I-485 (unbuilt)

Note: Click either tab below to toggle between I-20 and I-485 data and animations

BUILT: INTERSTATE 20

What was lost in Atlanta? How did I-20 devastate and transform the city, and the people within it? This animation visualizing before and after construction of I-20 using historic satellite imagery was produced in partnership with @Segregation_By_Design.

What was lost with the construction of Interstate 20 (within the city limits):

Also, roads are liabilities, not assets, and maintaining or rehabilitating them require significant costs. Highways are the most expensive kind of road to maintain due to their width, material (often concrete), and traffic volumes. Figures vary, but according to a Strong Towns analysis of 2014 FHWA numbers, it can cost upwards of $7.7 million per mile to reconstruct an existing lane of a freeway like this one.

Mayor Ivan Allen is widely credited with popularizing “The City Too Busy to Hate” as a slogan for Atlanta

This aerial view looking west shows the 75/85 Connector under construction from left to right, with a massive chunk of land being cleared and prepared for the east-west segment of I-485 segment which was then never built, lying fallow until repurposed for today’s John Lewis Freedom Parkway in the 1990s. Credit: The Atlanta History Center.

Progress was more mixed and uneven than the popular slogan suggested.

Life on Sweet Auburn after Interstates 75/85 were deliberately routed through this historically Black neighborhood in Atlanta, visible at the top of the photograph. Credit: AJCP145-014BH, Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographic Archive, Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library.

Looking east on Sweet Auburn in 2011. The historic Odd Fellows building is at left, one of the few spared by construction of the Connector, visible in the background. Flickr photo by Ken Lund.

The City Too Busy Moving to Hate

Today, crisscrossed by interstates that dispersed the metro area’s population and jobs, Atlanta is home to some of the worst traffic in the nation. The Tom Moreland Interchange—the complicated intersection of Interstates 285 and 85 and other roads on the north side, often called “Spaghetti Junction”—is consistently ranked as one of the top three worst truck bottlenecks in the nation. The state has created massive traffic problems by spending billions to disperse people, homes, and jobs. And today, they continue to try and solve the traffic congestion they’ve created by turning to the same “solution” that created the problems in the first place.

While some of the proposed highways were never built, the two examples we analyze from Atlanta are instructive for what does and doesn’t get built, and why.

© 2025 Smart Growth America. All rights reserved

Site By3Lane Marketing