Divided by Design

Part A: How today’s models, measures, and policies make things worse

Our current approach to transportation in the US—modeled by our national surface transportation program and mirrored in state departments of transportation and other transportation agencies—prioritizes fast, freeflow vehicle travel above all else and treats the people walking, biking, and riding transit as afterthoughts.

Measuring Traffic Flow

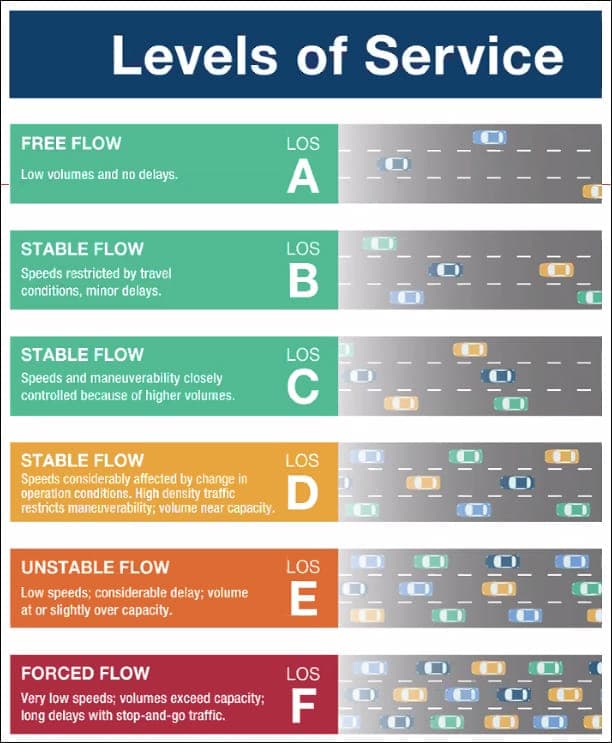

LOS is the most important way of measuring transportation that everyday people are unaware of. It is a qualitative measure of the operating conditions for motor vehicles on a roadway based on quantitative factors like speed, maneuverability, and delay.

A roadway is given a LOS score ranging from LOS-A, which means fully free-flowing open traffic, to LOS-F, meaning stop and go. Every agency or jurisdiction has a target LOS level, often a C. But some areas have lowered it, recognizing that a fully utilized road will, at times, have traffic.

For example, a downtown street through a busy area has a completely different purpose than a highway on the edge of town, yet LOS treats both the same way, with the goal being free-flow traffic. Level of service has been used (and still is) to justify costly widenings that make local travel more difficult in order to speed thru traffic through the same area.

The Fallacy of LOS as a Safety Measure

A group of neighbors, transportation officials and activists conduct a walk audit along Aurora Avenue, one of the most dangerous streets in Seattle, where 20 people have died in traffic collisions since 2015. Photo courtesy of Lizz Giordano and Crosscut.

© 2025 Smart Growth America. All rights reserved

Site By3Lane Marketing