Created by Design: Historic Inequities in U.S. Transportation

The devastation, disconnection, and displacement resulting from plowing highways through cities and neighborhoods is easy to see, but rarely do we quantify the costs in terms of lost wealth, land, residents, and businesses. In addition to the look at the history below in Part I, we also examine current and historical data on the impact of one built and one unbuilt highway in Atlanta, Georgia and Washington, DC in an attempt to quantify what was lost—and what could have been lost.

The Interstate age: Damaging divisions, created by design

History quantified: Examining the damage in Washington, DC

Highways built through cities have caused clear devastation, disconnection, and displacement, but the costs in lost wealth, land, residents, and businesses are rarely quantified. We analyze data on one built and one unbuilt highway in Washington, DC (and similarly in Atlanta) to measure both the actual and potential impacts.

History quantified: Examining the damage in Atlanta, GA

The visible devastation, disconnection, and displacement caused by highways through cities is clear, yet the costs in lost wealth, land, residents, and businesses are rarely quantified. We analyze current and historical data on one built and one unbuilt highway in Atlanta, GA to assess both the actual and potential damage.

From Convoy to Concrete: How Eisenhower's Vision for the Interstate Highway System Shaped Urban and Rural America

Recollection of General Bragdon, Secretary of Commerce and head of the Bureau of Public Roads, of an April 1960 meeting with Eisenhower

The Marginalization of Critics and the Rise of Suburbanization: How Post-War Policies Shaped Highway Expansion and Urban Change

A map of the Dwight D. Eisenhower System of Interstate and Defense Highways from the US Department of Transportation, which didn’t provide a detailed look at how highways would be routed and sited within cities. Credit: USDOT and FHWA.

How Interstate Highways Served Suburban Interests and Fueled Displacement: The Dual Role of Urban Freeways in Post-War America

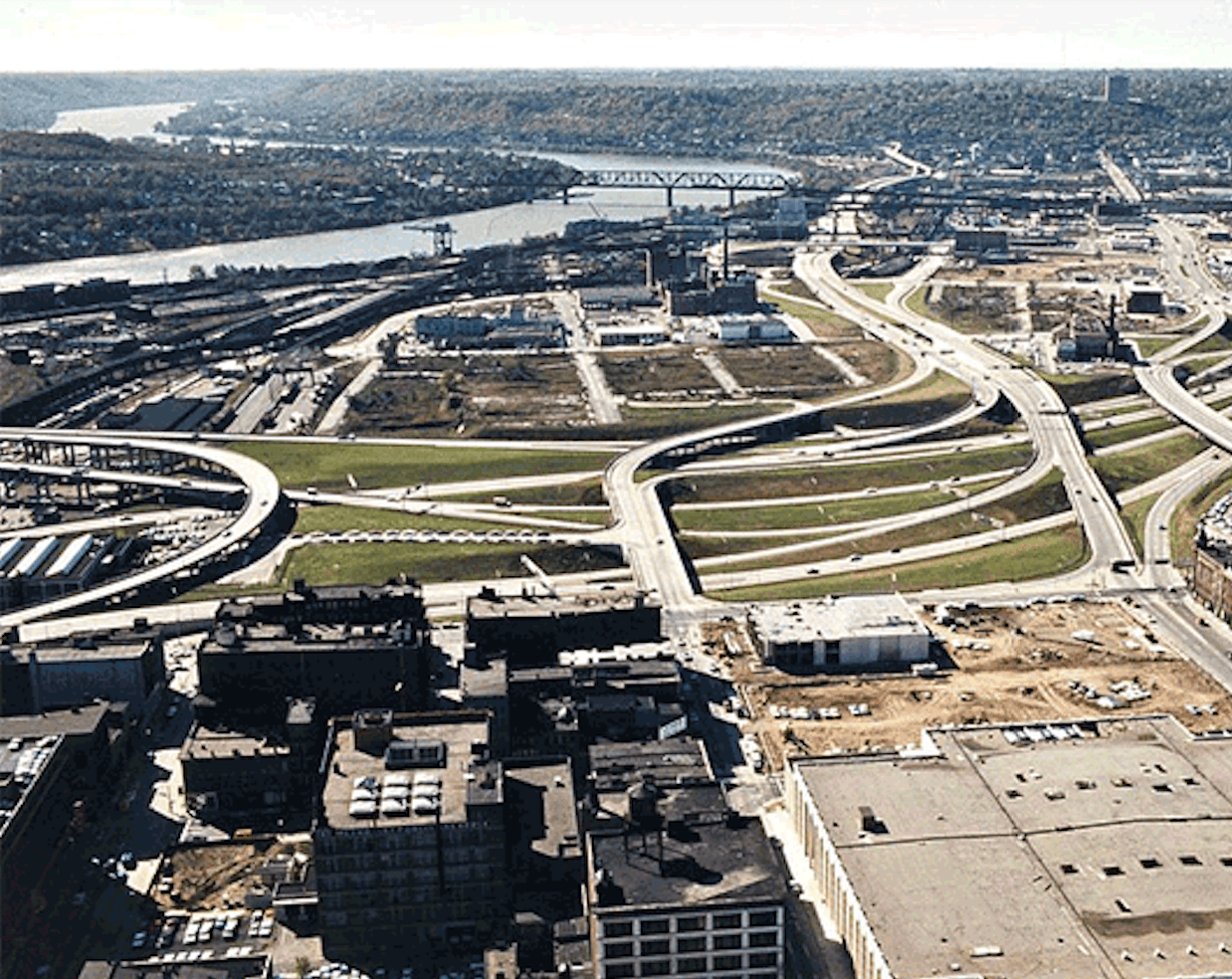

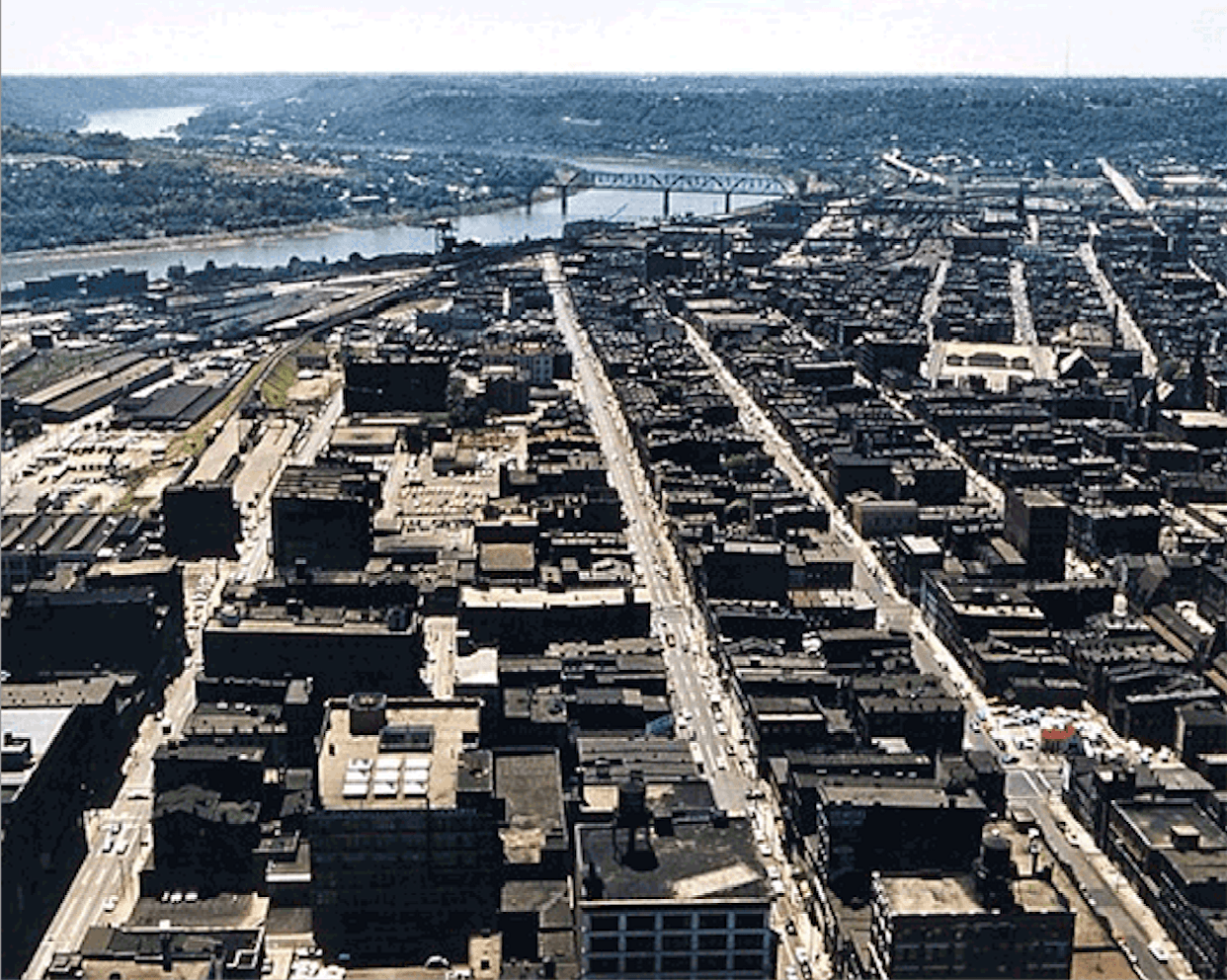

These photos from Cincinnati show how much destruction was wrought between 1958 (left photo) and 1966 (right photo) to build the interchanges for Interstates 71 and 75 just west of downtown.

Urban Renewal and Racial Displacement: How Highways Targeted and Destroyed Communities of Color

The D.C. Freeway Revolt and the Coming of Metro, Part Six.

In Alabama, Sam Englehart, who was also the leader of a hate group known as the Alabama White Citizens Council, became the Director of the Alabama Highway Department. In one of the most egregious but far from atypical examples, Englehart personally intervened to reroute I-65 through prosperous Black neighborhoods in West Montgomery, even intentionally targeting the home of civil rights leader Ralph David Abernathy for destruction. Residents of these communities lacked the political power needed to halt such projects.2

During the Senate confirmation hearing before the Committee on Commerce on January 15, 1969, several Senators asked about the nominee’s (John Volpe) views on highways and his actions as Governor. Senator Philip A. Hart (D-Mi.) told Governor Volpe that ‘in the eyes of minority groups,’ the Federal highway program ‘is an enemy, because they do not generally run the highway through my house or yours; it is the fellow whose property is cheaper, quicker to get, but who when he is moved has less opportunity to relocate successfully than you and I have.

When Congress approved the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, it authorized what was then the largest public works program in U.S. history. The law promised to construct 41,000 miles of an ambitious interstate highway system that would crisscross the nation, dramatically expanding America's roadways and connecting 42 state capital cities and 90 percent of all American cities with populations over 50,000. Its goal was to eliminate unsafe roads, inefficient routes and traffic jams that impede fast and safe cross-country travel.

During the Senate confirmation hearing before the Committee on Commerce on January 15, 1969, several Senators asked about the nominee’s (John Volpe) views on highways and his actions as Governor. Senator Philip A. Hart (D-Mi.) told Governor Volpe that ‘in the eyes of minority groups,’ the Federal highway program ‘is an enemy, because they do not generally run the highway through my house or yours; it is the fellow whose property is cheaper, quicker to get, but who when he is moved has less opportunity to relocate successfully than you and I have.

Highways as Tools of Segregation: How Urban Renewal and Design Choices Excluded Communities of Color

The interstate system has carved up cities small and large, rendering it either impossible or extremely dangerous to get around with a vehicle. Two people attempt to navigate an interstate frontage road without sidewalks in Jackson, MS. Photo courtesy of Scott Crawford.

Highways as a Legacy of Exclusion: How Historical Policies Shape Ongoing Transportation Inequities

Highways were just one part of a larger system of exclusionary practices put into place with the help of federal investment and policies. However, once highways were in place, they created a new set of unforeseen problems and costs, which federal, state, and local governments would be forced to grapple with for years to come, even to the present day.

This more openly racist past may be behind us, but that history still shapes the present. And the fact that our federal transportation program and most state transportation agencies were chartered or tasked with building new highways as their primary role for decades is the reason why a deeply held system of assumptions, measures, models, and other hidden factors continue to produce the same inequitable outcomes, regardless of the motives of those in charge.

© 2025 Smart Growth America. All rights reserved

Site By3Lane Marketing