Divided by Design

Part A: How today’s models, measures, and policies make things worse

Our current approach to transportation in the US—modeled by our national surface transportation program and mirrored in state departments of transportation and other transportation agencies—prioritizes fast, freeflow vehicle travel above all else and treats the people walking, biking, and riding transit as afterthoughts.

Current Priorities: A Focus on Vehicles

This focus on freeflow car travel is embedded in our transportation policies, funding structures, design and operational standards, and performance measures. It contributes to a feedback loop that results in disconnected, sprawling land uses, displaces economic development in favor of car movement and storage, creates significant congestion completely by design, and causes Americans to drive more and further every year.

The same standards and regulations first adopted during the construction of the national interstate system are still in use today and are applied on many types of roads

Value of time, delay, and congestion

When moving vehicles quickly on all roads is the number one goal for transportation agencies, congestion relief becomes paramount and agencies focus on time savings to drivers at the expense of nearly every other type of user or activity. One widely used federal measure that creates more damage and inequity is known as value of time guidance from the U.S. Secretary of Transportation, enthusiastically supported by the Office of Management and Budget.

The failure to measure or account for induced travel demand

Watch the four-stage cycle of induced demand in this gif above.

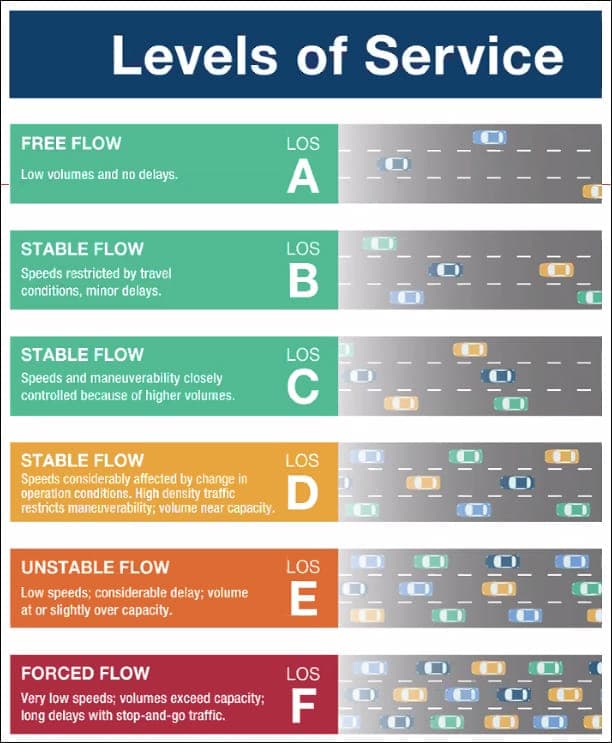

Level of Service

The assumptions contained in the value of time and delay can also be found in a basic design measure that is used to assess the performance of most roadway projects called level of service or LOS.

Forgiving street design, but only for drivers and passengers

Setting speed limits to prioritize those who would speed

Beth Osborne of Smart Growth America explains the dangerous way that speed limits are typically set using the “85th percentile rule” in this video created by the Wall Street Journal.

© 2025 Smart Growth America. All rights reserved

Site By3Lane Marketing