Divided by Design

Part B: The inequities produced by these policies and practices

The previous section described the current policies and practices that ensure our communities and roadways are designed to move cars as quickly as possible. Many of these practices have been inherited from the early interstate age, crafted in many cases by intentionally racist leaders who controlled the decisions about new highways and whose needs would be prioritized by the system overall.

Breaking the cycle of inequitable transportation

Today’s approach is shaped by the past, and it leads to many inequitable and harmful outcomes, including less opportunity for physical activity, increased traffic crashes, increased exposure to air pollution, increased greenhouse gas emissions, and higher household transportation costs. These negative impacts are particularly severe for the most vulnerable populations. To end this cycle, transportation agencies and elected leaders—at all levels of government—must start by understanding and acknowledging how the current policies and standards that guide their decisions are still damaging communities.

They need to understand how their current approach prioritizes certain people and harms others in order to transform that approach.

Car-oriented communities leave millions of Americans vulnerable

A 2018 survey from the National Aging and Disability Transportation Center found 40 percent of adults over age 65 cannot do the activities they need to do or enjoy doing because they cannot drive. 40 percent of the survey respondents cited access and availability of affordable transportation as a barrier, and respondents regularly described feeling dependent on others, frustrated, isolated, and trapped after giving up driving. An estimated 25.5 million Americans have disabilities that make traveling outside the home difficult, according to the Bureau of Transportation Statistics, and people with travel-limiting disabilities are less likely to have jobs.

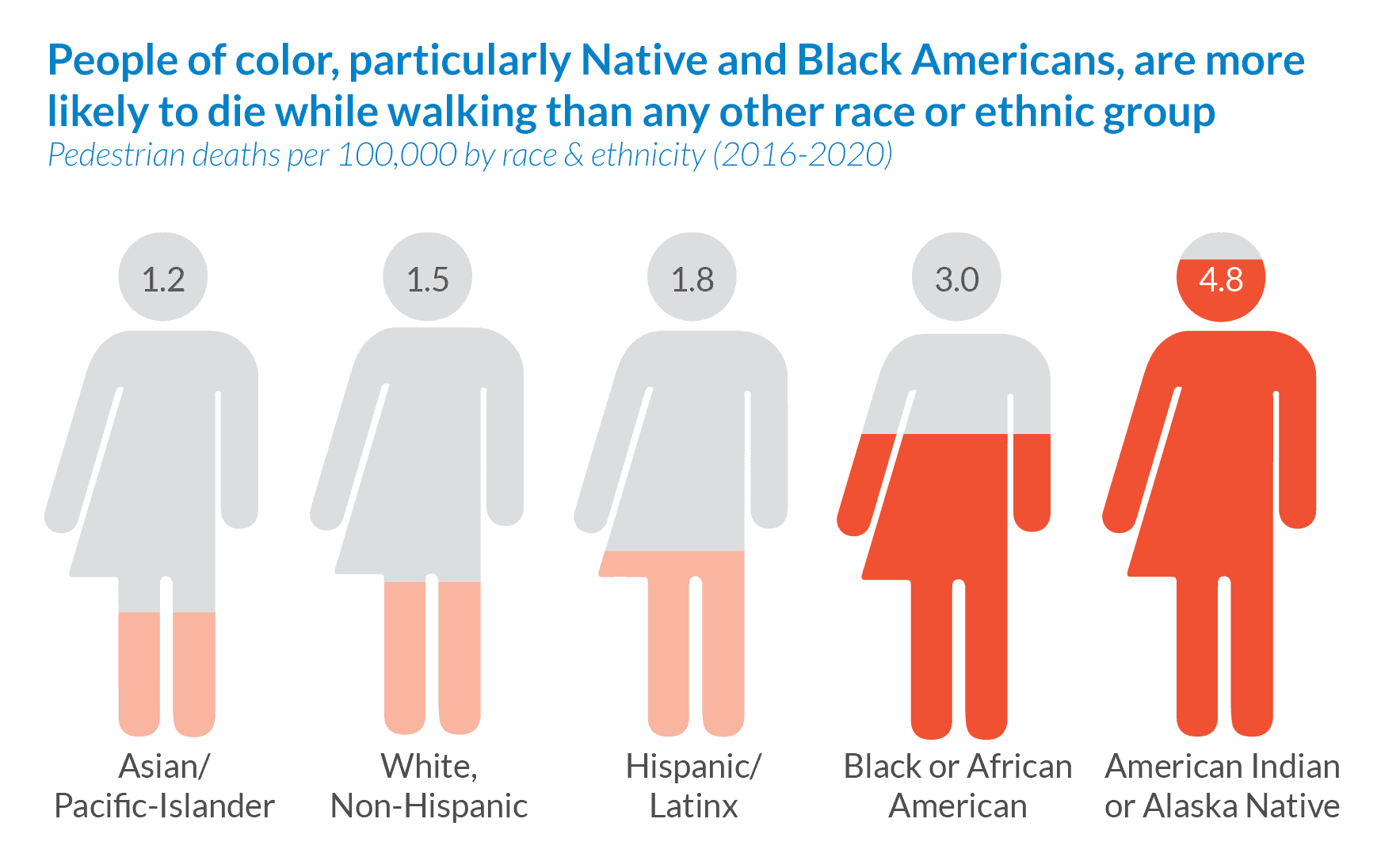

Our roads are deadly for people walking, especially for already-disadvantaged populations

A woman in a powered wheelchair tries to safely travel around Jackson, MS. Photo courtesy of Scott Crawford.

Speed or Safety

The design of our roads produces these dangerous conditions for people walking: wide lanes, large distances between traffic signals, and long unobstructed lines of sight make it feel safe to drive fast—often significantly faster than the posted speed limit—and drivers unconsciously follow these visual cues. For people on foot, the likelihood of surviving a crash decreases rapidly as speeds increase past 30 mph.

A racial and economic divide

A family walks along a substandard sidewalk next to Martin Luther King. Jr. Highway near Landover, MD.

Photo by Steve Davis, Smart Growth America.

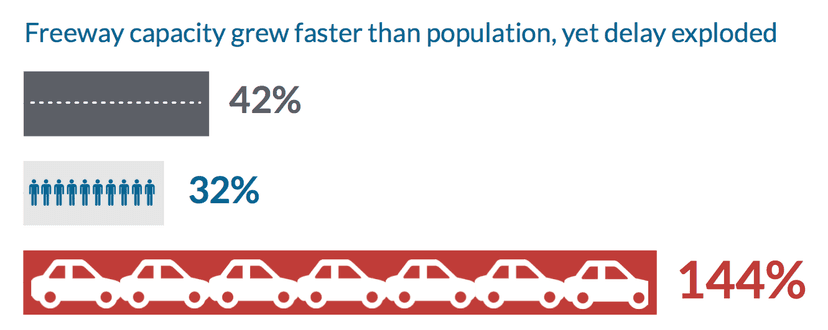

Growing traffic, more pollution, and poor health outcomes

Car-oriented development, embedded in our status quo approach, has had other negative consequences for American communities: more driving means more transportation emissions, more traffic, and often poor health outcomes. People of color and low-income communities experience these impacts at disproportionate rates.

Failure to supply the growing demand for walkable, transit-rich communities price out those who most need affordable transportation options

People dislocated by past highway projects are dislocated again

This has not stopped urban areas from continuing to expand highways. In the last three decades, more than 200,000 people nationwide have lost their homes to federal road projects. The overwhelming majority of people forced from their homes are people of color.

It is likely true that, as transportation planners maintain, highway expansions are less destructive than building new highways through cities. However, because highways were historically placed in communities of color, expanding these same roadways can only result in displacing members of these communities again.

© 2025 Smart Growth America. All rights reserved

Site By3Lane Marketing