Divided by Design

Part A: How today’s models, measures, and policies make things worse

Our current approach to transportation in the US—modeled by our national surface transportation program and mirrored in state departments of transportation and other transportation agencies—prioritizes fast, freeflow vehicle travel above all else and treats the people walking, biking, and riding transit as afterthoughts.

Value of time, delay, and congestion

Our current approach to transportation in the US—modeled by our national surface transportation program and mirrored in state departments of transportation and other transportation agencies—prioritizes fast, freeflow vehicle travel above all else and treats the people walking, biking, and riding transit as afterthoughts.

When modeling for time savings, agencies focus on only one thing: getting and keeping vehicles moving. As long as vehicles are moving faster, agencies predict that their new project will save time, which is nearly always assumed to be a net positive with economic value.

This video above, adapted from this section of Divided by Design, explains how value of time guidance is used to justify costly, damaging, divisive highway projects.

The USDOT specifies a percentage of hourly income that should be used to determine the hourly rate of time savings, down to the imaginary dollar, and then they multiply this by the number of commuters, resulting in huge but ridiculous numbers. But these are not “real” dollars, and do not result in commuters seeing actual cash returned to their pockets. After all, if you save a handful of seconds a month or a year, you do not receive actual cash in your pocket—it’s just theoretical money. And it doesn’t matter if, to speed up vehicles, daily trips end up being longer and taking more time overall.

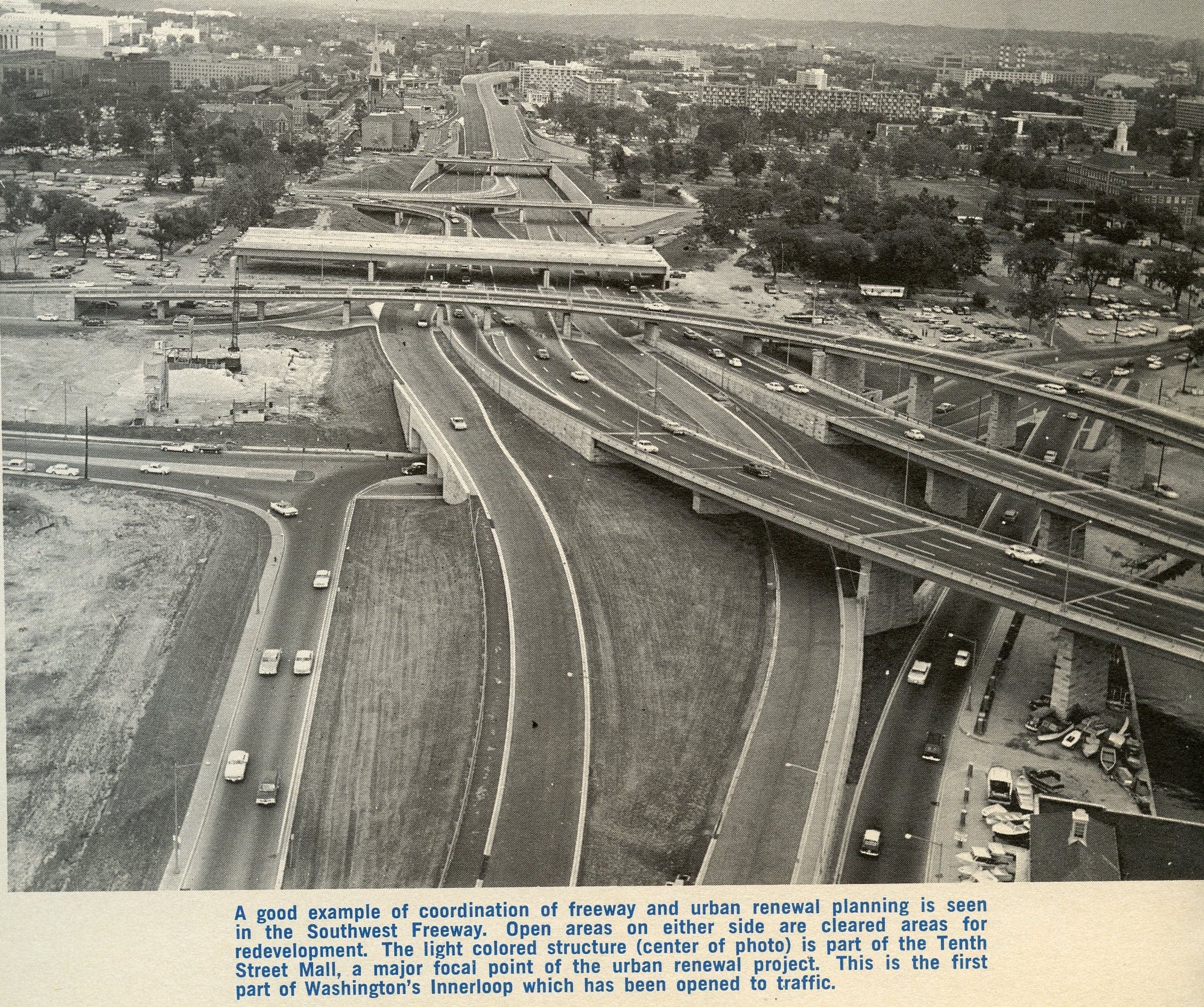

How the use of the “value of time” decimates communities

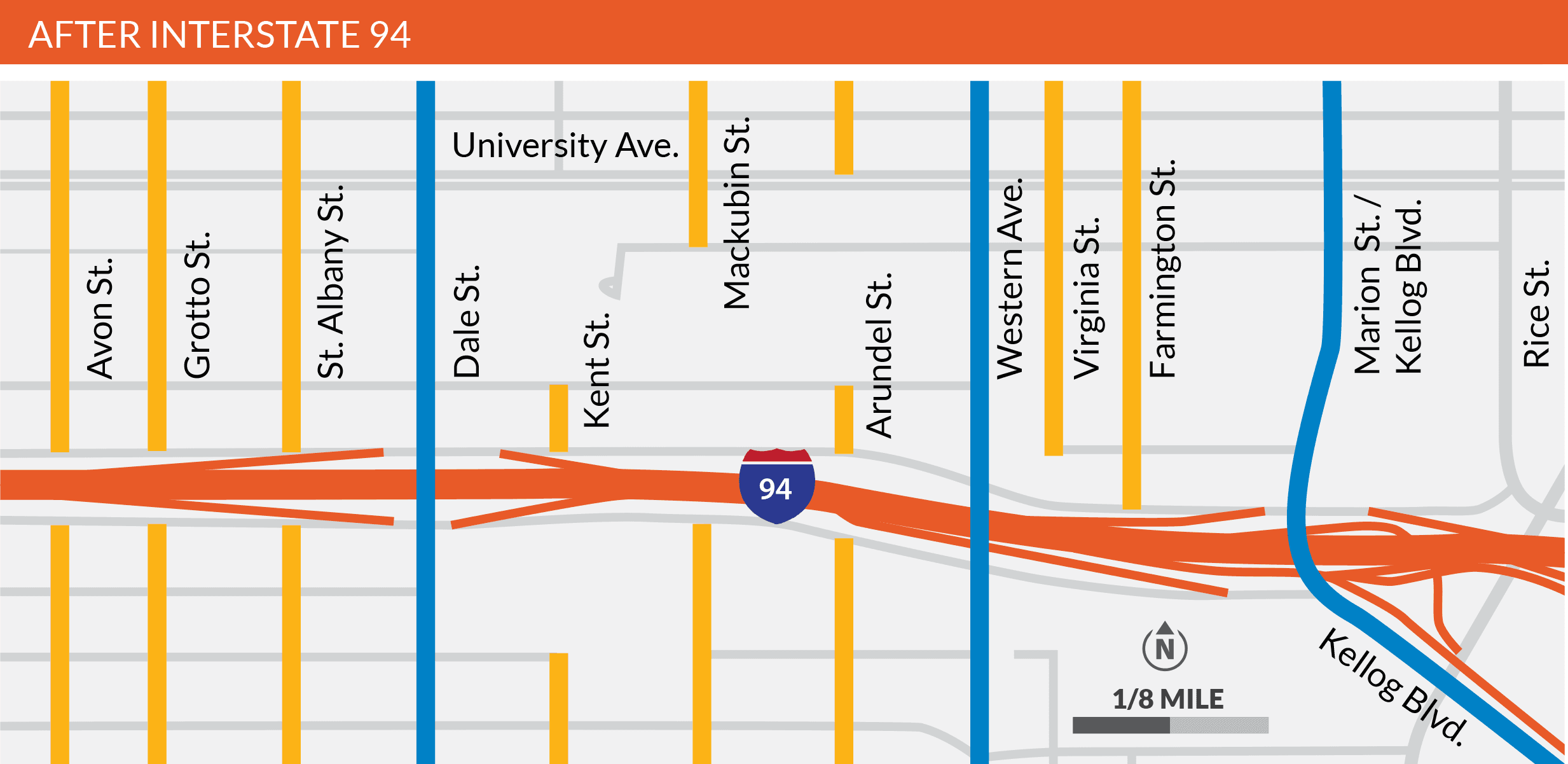

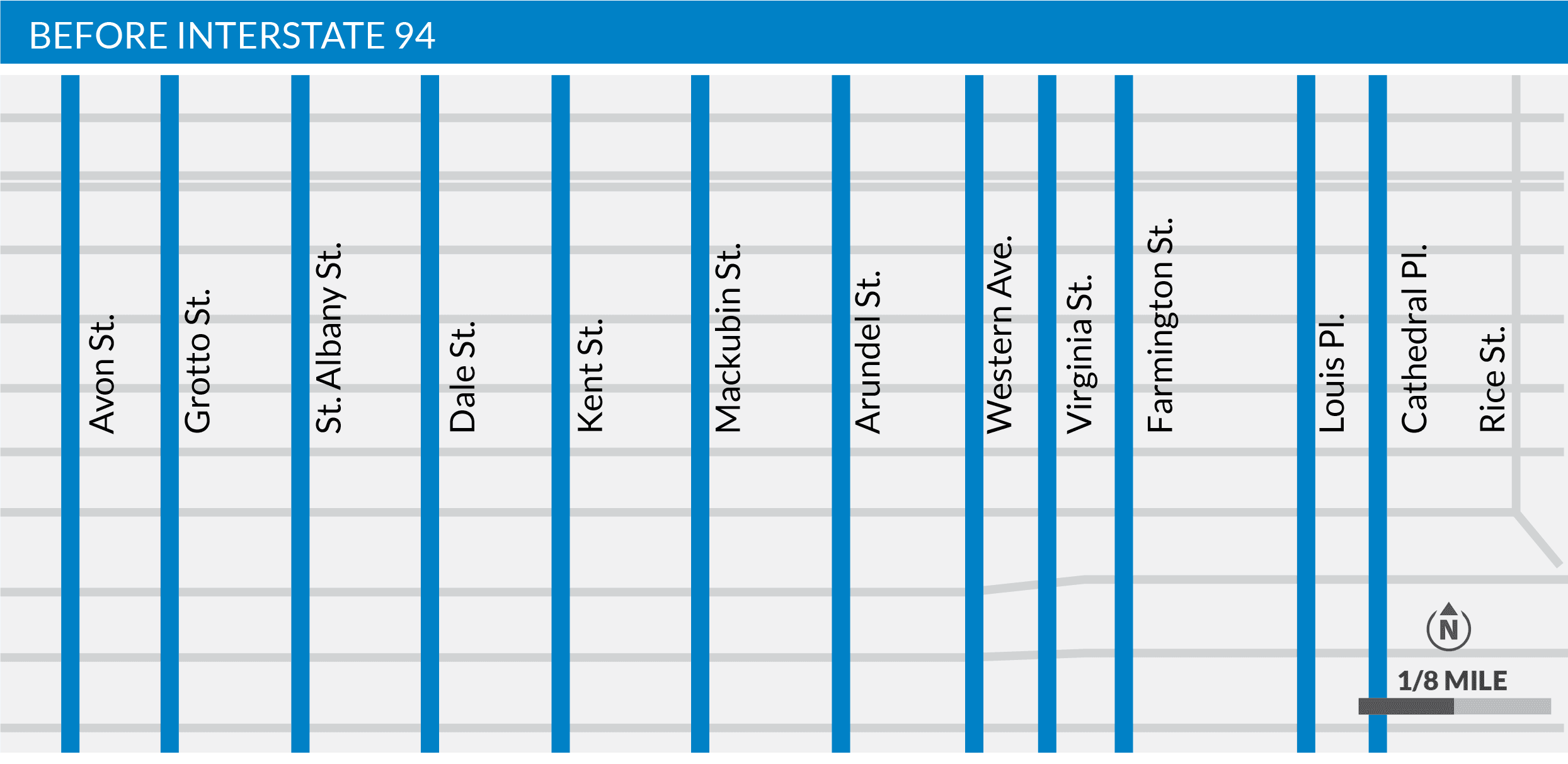

This example from St. Paul, MN shows how DOTs use the value of time to justify incredibly costly highway projects to save potential thru-commuters seconds per trip, while completely ignoring the impact of disconnecting these streets and making all other trips significantly longer.

Considering that in most urban areas, a greater share of people walking or taking transit are more likely to be lower- income or people of color, it’s easy to see how this value of time measure prioritizes certain people over others.

This rudimentary, outdated approach ignores the fact that travel time is a function of speed and distance

In looking at only speed in this way, the federal government allows a project sponsor to take credit for saving travelers’ time even if the project:

- Lengthens the distance of travel for drivers on the corridor and adds to travel time (e.g. disallowing left-hand turns, requiring a roundabout trip);

- Creates delay for people traveling across the corridor (e.g. creating gaps or disconnections in the adjacent street network);

- Creates delay for people crossing the corridor on foot or bike (e.g. removing crosswalks or intersections producing longer trips on foot, increasing the road width.)

© 2025 Smart Growth America. All rights reserved

Site By3Lane Marketing