Divided by Design

Examining the damage in Washington, DC

The devastation, disconnection, and displacement of highways plowed through cities and neighborhoods is easy to see, but rarely do we quantify the costs in terms of lost wealth, land, residents, and businesses. The damage also could have been much worse, with many planned highways never built or completed. In this article, we examine current and historical data on the impact of one built and one unbuilt highway in Washington, DC.1

Washington, DC’s Story

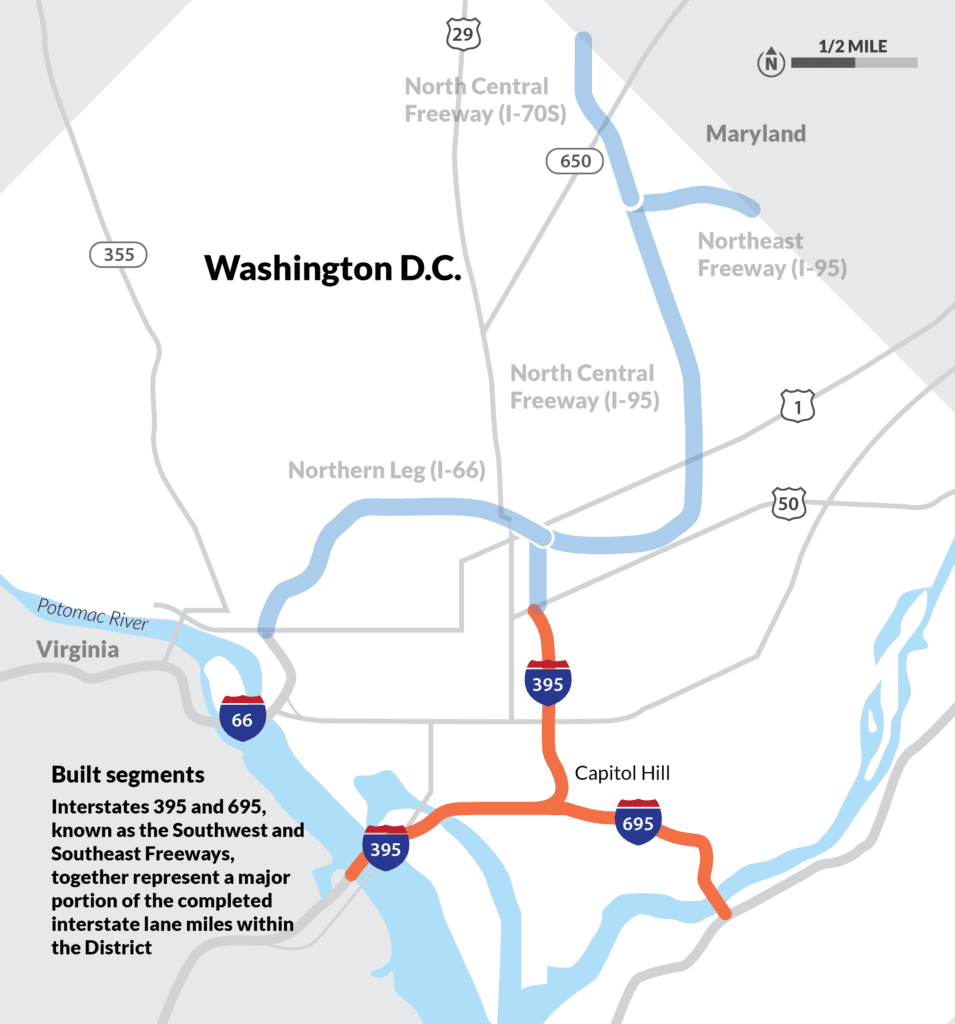

I-395/695 (built) and I-95/66/70 extensions (unbuilt)

Note: Click either tab below to toggle between I-395/695 and I-95/66/70 data, and animations

BUILT: INTERSTATES 395/695

What was lost in DC? How did these interstates devastate and transform the city, and the people within it? This animation visualizing before and after construction of I-395/695 using historic satellite imagery was produced in partnership with @Segregation_By_Design.

What was lost with the construction of I-395/695 (within the city limits):

Also, roads are liabilities, not assets, and maintaining or rehabilitating them require significant costs. Highways are the most expensive kind of road to maintain due to their width, material (often concrete), and traffic volumes. Figures vary, but according to a Strong Towns analysis of 2014 FHWA numbers, it can cost upwards of $7.7 million per mile to reconstruct an existing lane of a freeway like this one.

How 1950s and 60s Highway Plans Ignored DC's Needs, Fueled Suburban Sprawl, and Threatened Historic Neighborhoods

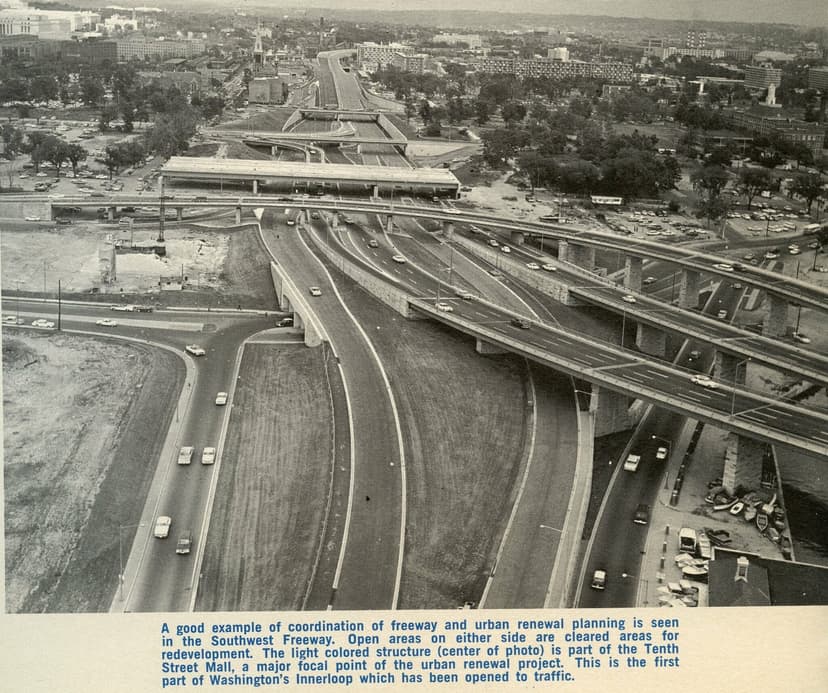

Credit: District of Columbia, Department of Highways and Traffic and District Department of Transportation, “Southeast/Southwest Freeway,” DDOT Historic Collections, accessed June 13, 2023.

Despite Successful Coalition Efforts, DC's Black and Blue-Collar Neighborhoods Suffered Devastation from Highway Construction and Urban Renewal

In an aerial photo looking to the east, land has already been cleared for the next few blocks of the Southeast/Southwest Freeway (I-395/695).

Credit: District of Columbia, Department of Highways and Traffic and District Department of Transportation. “Southeast/Southwest Freeway.” DDOT Historic Collections, accessed June 13, 2023.

Historic photograph of an ECTC meeting. Credit: Washington Post. DC Public Library Star Collection.

© 2025 Smart Growth America. All rights reserved

Site By3Lane Marketing